Posted on:

My checklist for bringing a website to production

To reach a production environment, many more items that may be out of a developer's scope have to be reviewed, so here is my production-ready checklist for easy reference.

The article below is my personal note on what to consider before putting a website into production. It is certainly applicable to this website, hungvu.tech, but your mileage may vary depending on the requirements of your application.

Read the “production checklist” of the chosen technology stack documentation

Most likely, the documentation of the technology you use has a “production checklist” somewhere. Reading documentation is a very good starting point. Let’s have a real example, the core technologies behind my website are Next.js, Payload CMS, MongoDB, Cloudflare, AWS, Docker, and Caddy. There are specific points to look out for.

What is the interaction between technologies if I combine them? For example,

- What do I need to consider when hosting Next.js using a Docker container?

- What happens when I put the Payload CMS backend behind a layer 7 reverse proxy like Caddy?

- Do I need to connect Payload CMS to MongoDB in a specific way?

- What happens when running Caddy on an EC2 instance, with traffic proxied through Cloudflare?

- What is the security consideration, considering that the application is facing the public Internet now?

- What is the performance consideration? For example, hardware specification, traffic behavior, and more.

As you can see, these points are very high level, and as I think more about them, a lot more questions showed up and led me to some corners on GitHub discussion, community-specific platforms (like Payload CMS Discord server), and so on.

Now, let’s review my personal checklist, in no particular order.

Metadata

Thinking about the word “front end”, I mean it for both “front of the front end”, and “front of the back end”.

This blog is built with Next.js, which is capable of both delivering HTML/CSS/JS content and operating its own API routes. In this context, I say the HTML/CSS/JS part is the front end of API “front-end” routes, hence “front of the front end”. Meanwhile, my back end, which Payload CMS powers, has its admin dashboard. I call this admin dashboard “front of the back end”.

Every front end has its metadata information. Overall, they are used to support crawlers, and clients in understanding what the website is about. For a blog site, I need 4 types of metadata.

The first is represented by meta tags.

- Charset

- Viewport

- Theme color

- Description

- Google site verification

- Open graph (og)

The second is other important tags inside the head element.

- Title

- Canonical link

- Favicon

The third one is Schema.org JSON-LD. I actually question the usefulness of this feature, but if it is relatively easy to implement without a glaring downside, just give it a shot I guess? In Next.js, there is next-seo package that greatly simplifies the implementation of Schema.org JSON-LD.

The last one is not an HTML element, instead, it consists of special files that affect how the web crawlers see your page.

- Robots.txt

- Sitemap.xml

- RSS.xml (my website currently does not have this, but may in the future)

Caching

In Next.js

The modern version of Next.js supports caching fetch requests, so that raises a few questions.

- Which request should be cached?

- What should be the cache duration?

- Should the cache be ephemeral or persistent?

Keep in mind, as of Next.js v14.0.4, the cached response size limit per request is 2 MB. Exceeding the limit will error out the fetch request, hence making this feature useless (or at least, not intended for) large responses. Caching larger responses, in combination with Next.js images, is resource-intensive. At the moment, I cannot say if this is an error from my implementation or not, but I can say the caching mechanism did hammer down my CPU, RAM, and bottleneck IO throughput of my EC2 instance.

Besides, I make my Next.js cache ephemeral so that every time I update the web service image, the stale cache is purged when creating a new container, ensuring my website is always up to date.

In Cloudflare

There are many layers of caching in web development. Aside from the Next.js system, hungvu.tech uses Cloudflare (a content delivery network) as a second cache layer. This brings up certain questions.

- Is Cloudflare caching at the moment? This can be confirmed by monitoring Cloudflare statistics or observing the cache header of the response. I recently noticed the cache hit rate of my blog suddenly dropped and am investigating the issue.

- If an issue is observed in production, is it due to the Cloudflare cache? The issues are variable, from cross-origin resource sharing, and no response request, to broken layout (due to Cloudflare “optimization” like Rocket loader, auto minify), and more. In my experience, purging the cache does not always make the website up to date, it is better to enable Development Mode to completely bypass the Cloudflare cache layer to troubleshoot the issue in real-time.

Security

I’m not a security expert by any means, so I do not want to pretend I know the ins and outs of the items mentioned below. There are plenty of deep-dive articles out there such as those from Mozilla documentation, so this list is, well, just a checklist. It is best to search these keywords below in your technology stacks documentation, I bet they do have a section regarding reference implementation somewhere.

Access control list (ACL): This goes without saying. ACL exists at multiple layers.

- Software-wise, some notable ones are navigation route protection, API rules, identity-aware proxy, and identity access management.

- Hardware-wise, there are physical, network (North-South and East-West traffic), and host protection. Really, defense in depth is a very specialized topic and I am still learning more about it over time.

Content Security Policy (CSP): This helps the front end mitigate certain types of security issues. Cross-origin resource request (CORS), same-origin policy (SOP), and cross-site request forgery (CSRF): Similar to CSP, these are presented to mitigate common attack vectors. These concepts are not the same though, but in my experience, they often belong to the same section in a documentation. Rate limit, IP blocking,** and CAPTCHA: **These exist to mitigate bot traffic and API abuse issues. There are good bots like search engine bots, but the majority are bad bots that exist to exploit websites. Rate limit, IP blocking, and CAPTCHA are prominent ways to fight against bad bots. There are some things to consider though.

- Rate limit and IP block can be applied at different layers. In my case, Cloudflare, Caddy, and Payload CMS (with Express underneath) do have their own implementation for rate limit and IP blocking.

- IP block may not behave as expected when traffic is proxied through multiple layers such as Cloudflare and Caddy at hungvu.tech.

- CAPTCHA may affect real user experience and their privacy, so use it at your judgment. At the time of writing, my blog does not have CAPTCHA implemented.

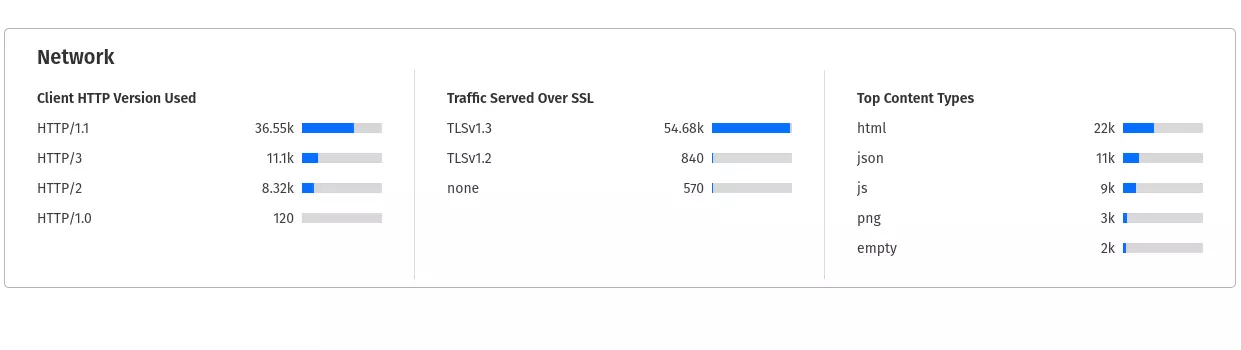

Trust proxy: This in Express.js, and equivalent features in other frameworks, is used to specify configuration when the web server is behind a reverse proxy. The setting itself can have security implications. **Secure Socket Layer (SSL) and Transport Layer Security (TLS) for Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS): **SSL was deprecated about 2 decades ago, and its successor is TLS. That said, people still use both terms interchangeably nowadays, even in the Cloudflare dashboard, hence the confusion. Just keep in mind that even though they all use the keyword “SSL”, products on the market right now are pretty much TLS only. Anyway, simple TLS and HTTPS are the main reasons why I use Caddy in the first place. There is one thing to consider.

- What does the encryption tunnel look like in a full round trip? In my case, a high-level view of traffic order is as follows: Client browser, then Cloudflare, then origin server (Caddy on port 443), then Next.js server, then Payload CMS server, and back. With my website, the priority is to have traffic between the client browser, Cloudflare, and the origin server fully encrypted. Internal traffic on the server is a different story though.

Performance

Caching itself should belong under this performance section, but I consider it important enough to be in a dedicated section. Now, performance is a measurable metric, and there are various aspects of an application that can be optimized using the said benchmark. The list below is just agnostic items that help improve performance on paper. Are they really useful? It is unknown until there is a benchmark.

HTTP/3 and QUIC: The third major version of the HTTP protocol, and is said to greatly improve performance along with many other improvements compared to HTTP/2. This is another reason why I use Caddy as a reverse proxy, as it supports HTTP/3 and QUIC protocols with just a little configuration. But, like SSL/TLS/HTTPS, there are a few things to consider.

- What does the request look like in a full round trip?

- What happens when one part of the chain is not HTTP/3 and QUIC supported? For encryption, I can say if a chain is broken, then that specific part is unencrypted and comes with security implications. For network protocol though, a benchmark will be helpful here.

Compression: I use the term compression loosely here, and below is what I mean

- Request/response compression: This category includes gzip, ztsd, and Brottli. They have reduced the size of the response, but I also need to consider how the compression is applied when there are many layers in-between (as discussed with HTTPS, and HTTP3). Besides, compression means increasing server load, so if not configured properly, the compression can slow down response time.

- Image optimization: Broadly said, this is static asset optimization, but when coming to images specifically, the two widely used compressed formats are AVIF and WebP.

Request and response size: This is an issue when the application overfetches. It may not be a glaring issue in a local development environment, but in production where applications are deployed to cloud services (or on-prem servers), it is a real deal.

- Bandwidth costs money, and latency can heavily affect performance.

- By default, applications and anywhere that requests and responses go through, have a limitation on request and response sizes. For example, Next.js fetch cache limit, and Payload CMS max allowed JSON body size are default to 2 MB. Without proper configuration to lift the limits, it can cause unexpected behaviors or outright crash the applications.

Frequency of requests and responses: In addition to the size mentioned above, frequency is also a factor.

- Frequent requests and responses mean increasing bandwidth usage.

- This can create an increased load on the host, leading to unexpected side effects. For example, the Payload CMS editor has an autosave feature and defaults at 800 milliseconds. The default is fine in the local development environment but breaks down in production. I changed the frequency to 15 seconds and issues are resolved.

Host machine architecture and specification: This is less of an issue for containerized applications as they can run on different CPU architectures. From my research, AWS’s general purpose offer on ARM is more performant than x86 alternatives. Anyway, hungvu.tech is containerized on an EC2 t4g.micro instance (as nano lacks memory), which is an ARM platform powered by AWS Graviton2 processors. There are some required steps to create an ARM image though, but it is greatly simplified using Docker GitHub Actions.

Potential bugs in compiler/transpiler and bundler

Here is a thing, to make the application production-ready, the source code must go through a compilation process of some sort. In Next.js with TypeScript, the bundling and transpiling process are required. Going through the process means the source code is transformed and optimized by the framework bundler and transpiller. If you can fully control the process, great. In reality, these processes are abstracted away to improve developer experience, and that by itself is a double-edged sword.

- What if the bundler and compiler/transpiler are “stealthily” broken?

- What if the bundler and compiler/transpiler conflict with your code base?

Considering the criticality of these components, they are mostly stable, but there is always an exception. For example, the Next.js production build can potentially mess up the front-end layout due to unexpected CSS ordering. This has been an ongoing issue since 2020 and is not fixed as of the latest version (Next.js v14.0.4). References are as below.

Wrap up

So, the list above is what I consider before bringing the application to production. The items, I suppose are all over the place, from software layer to infrastructure consideration. That’s why I created the article to consolidate my thoughts for future reference. Is it the best and most accurate list? Certainly not, because each project has its own goal and looks at matters differently, so the points above are mostly personal to me. I hope it is useful to you, but remember to treat the list with a grain of salt.

If you find this article to be helpful, I have some more for you!

- Virtualize TrueNAS with Harvester (and Kubevirt for VM management)

- Deploy a virtualized OpenWRT firewall in Harvester, how did it go?

- Is Harvester a good hypervisor for a beginner? My hands-on experience

And, let’s connect!